Alone in the Dock

Alone in the Dock

There, in front of the prisoner as she was brought up from the cells to the court room dock, were Messrs. Poland and Montagu Williams for the prosecution. At the lawyers’ table with them were Sir John Holker and Mr. Mead, her defence team. It was very crowded in the learned pit as the hospital’s Treasurer and its Governors were represented by Mr. Baggalley and his team; and the medical staff, not to be outdone, were represented separately by Sir Hardinge Gifford.

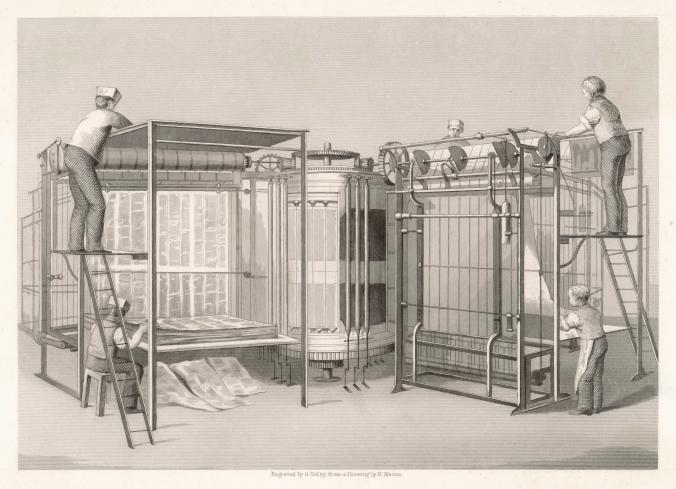

Looking up, the prisoner saw the reporters packed into the public gallery. The newspaper industry had expanded rapidly as massive new technology had shifted the printing process to a scale unimaginable only a few years earlier.

The Applegath printing press, as used by ‘The Times’ and by the ‘Illustrated London News’. Date: 1851

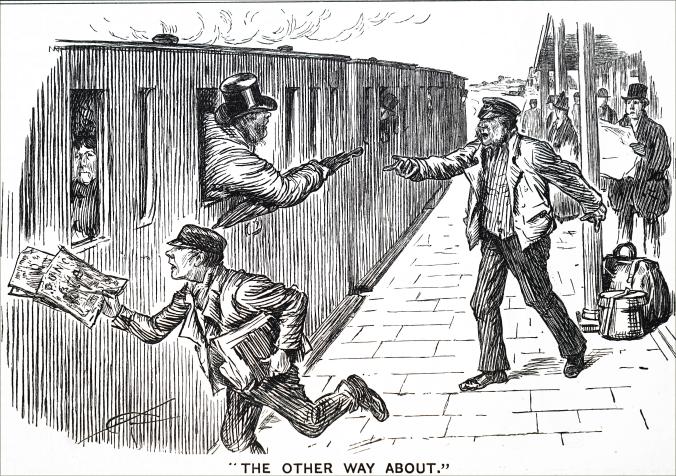

The public loved its news, especially crime, and the many Dailies and Weeklies carried much detail of the Old Bailey trials. News from the premier publication The Times of London was syndicated to the local provincial papers who reprinted the stories the next day helped by their rapid transit in the ever-expanding railways.

Illustration depicting London paper boys chasing a train to make a sale to passengers. Dated 19th century

This trial was a sensation. A nurse accused of killing a patient at one of London’s top hospitals. Was she incompetent? Was she cruel and negligent? Was she brutal? And there were other issues below the surface. Had the accused been a follower of the new trend known as “modern nursing”. Had she usurped the authority of the doctors as a result of counter instructions from the modernising Matron? Was she part of that noisy women’s movement?

The nurse in the dock looked out to a sea of inquisitorial faces and felt their chill. The proceedings began when the clerk of the court ordered all present to rise for the judge who was about to enter the court. No sooner had the judge opened the proceedings, there was a commotion in the pit. The lawyers were arguing with His Honour, Judge Hawkins, about the use of an important document, the Clinical Report of the case of the deceased. Its author, the hospital’s Mr. Beech, had not arrived in court. Sir John asked for a delay while he was found. A search was ordered.

The Accused was Feared

Opening for the prosecution, Mr. Poland called the deceased’s husband, Charles Morgan, to the witness box. His wife, Louey, had been admitted on the 9th June. Charles and his brother were working men, but they had visited as often as they were allowed. Louey was reportedly in good spirits until the 7th July when Charles had noticed bruises on her arms and chest. He had had words with the accused as she was Louey’s nurse. She had replied that it was a bad case of “hysteria”. He had asked the doctor, the great Dr. Frederick William Pavy, if he and his brother could visit more often.

The accused heard Mr. Morgan’s account of Louey’s complaints about her. His ‘poor wife’ had grown to be afraid of her nurse and she dreaded seeing her come along the ward. Louey went downhill and died on the 21st July.

So there was the accusation. A patient of Dr. Pavy had died after suffering what seemed to be severe bullying from her nurse. By implication, this is what you get if you adopt “modern nursing”.

Trapped in a Whirlpool

The accused found herself in another whirlpool of legal procedures. Leading up to the trial, the previous two weeks had seen the accused appear at the Coroner’s Court where she had given a detailed account of the events leading up to Louey’s death. She had been represented by Mr. Taylor, a local solicitor, who had helped her to make a sworn statement of the facts.

The hospital’s administrator, known as Mr. Treasurer, had presided over the institution’s internal inquiry and had concluded that the nurse had made errors of judgement for which she was instantly dismissed. She was then arrested for the crime of manslaughter by negligence.

A Hostile Press

The newspapers were full of the story as was the medical press which had been running hostile articles and letters about the hospital’s “modern nursing”, and the growing threat of “lady nurses”, since the arrival of the new Matron seven months earlier.

The newspapers were full of the story as was the medical press which had been running hostile articles and letters about the hospital’s “modern nursing”, and the growing threat of “lady nurses”, since the arrival of the new Matron seven months earlier.  Indeed, the public had been well-primed for the trial, especially when the nurses who would not sign up for the changes were sacked en masse. They formed a perfect narrative for the tabloids – a line of dismissed nurses, with their cases, leaving the hospital’s front quad through its great gates. This scandal was the result of “modern nursing” they cried.

Indeed, the public had been well-primed for the trial, especially when the nurses who would not sign up for the changes were sacked en masse. They formed a perfect narrative for the tabloids – a line of dismissed nurses, with their cases, leaving the hospital’s front quad through its great gates. This scandal was the result of “modern nursing” they cried.

Sir John’s Ace

The Coroner’s report formed the basis of Sir John’s defence, for it laid bare the circumstances of how Louey had come to be so bruised. The bruises had not been inflicted by a brutal nurse. They had been sustained in the course of a bath for the patient who had soiled herself. The temperature and depth of the water were important. The time the deceased was in the bath and how she had got into it were important. The level of assistance the patient, who was very weak and infirm, was given to get to the bathroom and back to her bed were important. Sir John would call upon the Coroner, Mr. William John Payne, to give a detailed account of these facts.

Then there was that Clinical Report. If the Judge agreed it was admissible, it would highlight to the jury the doctors’ diagnosis and prescription for Louey, and how this information was communicated to the nurses. The Defence would shine a light on the gaps in understanding between the doctors and the nurses on the ward, and how assumptions were made about Louey’s care, including whether the bath was part of the patient’s treatment. Important questions about the nature of medical expertise would need to be examined. And Sir John had an ace up his sleeve. The hospital’s senior doctors were worried. They knew the contents and importance of that Clinical Report, and they wanted their representative, Sir Hardinge Gifford, to ensure that it stayed confidential.

Was the accused incompetent, cruel and brutal? What was Sir John’s ace? Why was the great Dr. Pavy so worried?

Come back next time to hear the Case for the Defence.