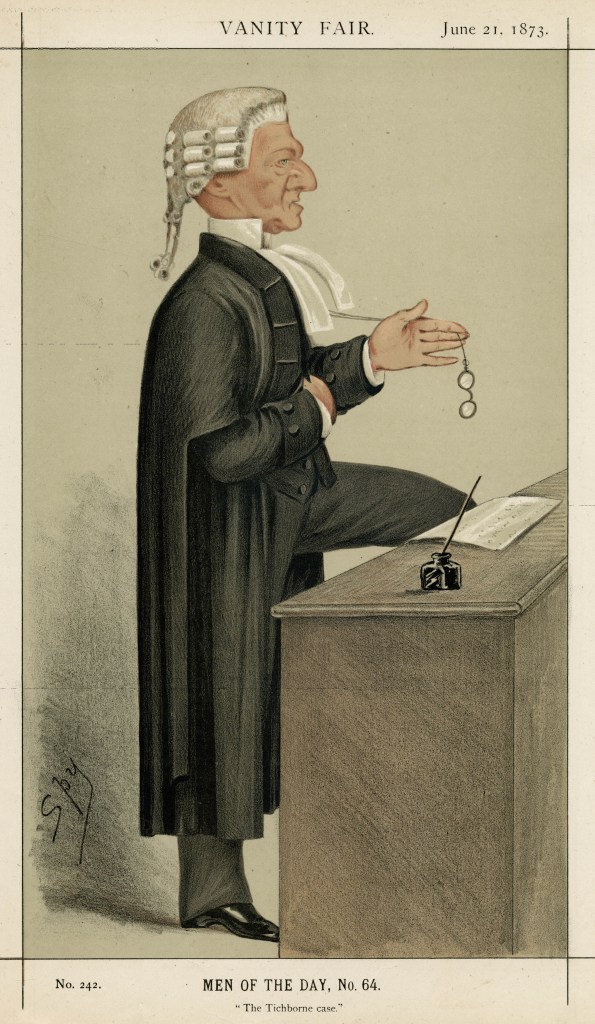

Sir William Gull’s Testimony

To everyone’s surprise, including Dr. Pavy’s, Sir William Gull, the Queen’s physician, was called for the defence. Sir William had been a senior doctor and colleague of Dr. Pavy for many years and was now the Senior Consulting Physician to the hospital while he concentrated on his private practice and royal duties.

At the request of Sir John, Sir William made himself “acquainted with the details of the case,” and “perused the clinical report very accurately.” He had not spoken to any of the doctors involved.

His confident testimony concerning the symptoms and diagnosis of tubercles on the brain – loss of power in the limbs and inability to control the bowels – supported his belief that Louey had been suffering from a terminal disease of the brain, not hysteria. Sir William stated that an experienced physician would have known the difference. Gasp.

Sir William’s testimony discounted any relationship between the bath and the patient’s death. Tellingly, he asserted that the best judge of the state of the patient ought to be the physician who sees the patient from day to day so “he can descry the difference in the patient on the one day between what is done in that case, and what is alleged afterwards.”

Clearly Sir William did not think Dr.Pavy had done his job properly as he stated “in this case I should certainly put my judgement against the judgement of the physician who attended the case from commencement… I would put my opinion against that of Dr. Pavy.” Gasp.

Condemnation of Dr. Pavy

Turning to the clinical report prepared by Dr. Pavy’s clerk, Mr. Veitch, a student, Sir William accused Dr. Pavy of bad practice for leaving the case wholly to Mr. Veitch and, as a consequence, failing to inquire into the details. Best practice, according to Sir William, was for the attending physician to dictate and check the notes after each examination; he had a duty at least to see the notes. Gasp.

What a condemnation of a fellow doctor. Professional incompetence. Dr. Pavy was apoplectic with rage, especially as he, and colleagues, had strenuously tried to have the clinical report kept in camera in the medical school, refusing to hand it over to the court. They feared doctors would be on trial for incorrect diagnosis, not the nurse.

It was left to the hospital’s medical superintendent, under the court’s instruction, to search the medical school premises and find the notes, which were handed over to the court.

Questions for the Jury

On the one hand, we have testimony that the accused nurse was cruel to the patient and that Louey’s bruises and death were due to her negligent care in administering a punishing cold bath. On the other, we have evidence, including from a nun, that the accused had shown great kindness and patience in assisting a very ill patient to have a cleansing bath. The jury was told that Mary ward was very busy and that there were too few staff on duty to do everything that was required.

All this took place in the context of an unclear diagnosis and confused instructions from the medical staff to the nurses. The initial diagnosis of “hysteria” as recorded by the clerk went unchecked, thus reducing the focus on Louey’s symptoms. There was also an accusation that the senior physician in charge of the case was not paying it the attention it required.

What happened on Mary Ward? For the jury, the key questions included:

- Did the cold bath kill Louey?

- Was the accused nurse intentionally cruel?

- Was the accused Louey’s killer?

The Outcome

Guilty

The jury added “we think there has been shown negligence on the part of the nurses, and that there should be a better supervision by the medical officers of the hospital.”

The sentence: Three Months’ Imprisonment, without hard labour.

This punishment seems to reflect the judge’s unease at the verdict. A spell in prison was inevitable after a manslaughter verdict but this was a very short sentence. Perhaps it was a case of something must be seen to be done.

Another Trial?

While the accused served her sentence, Dr. Pavy’s rage fuelled another trial through the summer and autumn of 1880. He, as a senior officer of the Royal College of Physicians, requested that Sir William be brought before its court to be censored and disbarred for “casting an imputed charge of professional incompetence on a professional brother.”

Many letters, both public and private, were exchanged casting the hospital in a very poor light. Its governors and the administrator stepped in to calm the feud. Sir William defended himself robustly accusing the College of over-reaching itself as it did not have the powers it claimed to proceed against him. It became a Mexican standoff. Dealings behind the scenes eventually closed the case before the Royal College. But the fact that one senior physician had so publicly attacked another’s competence resulted in a Parliamentary Inquiry. The dispute, on many levels, just kept on going despite the efforts of the hospital’s governors and administrator, and the Royal College.

And of the accused? She served her sentence and returned to nursing in South London, before making her way to India, to Calcutta, where she seems to have prospered, according to local probate records.

End note: There is much more to this story and those of the accused, the Matron and her new “lady nurses”, the administrator, Dr. Pavy and his medical colleagues, and Sir William Gull.

The complex intersection of the underlying tensions – gender politics, shifting boundaries of medical authority, and religious intolerance – are told in my forthcoming book.

For now, I’m going on writing leave to finish it. You can follow its progress in a new blog series starting next month:

Postcard from a Seaside Garden . . .